Modeling to make the perfect brownies

Normally it requires lots of computations involving partial differential equations, however I came up with a different method to model the heat in a brownie pan.

The Problem

For my Math 227 (mathematical modeling) class at the New Jersey Institute of Technology, the final project of the class involved completing one of the problems from the Mathematical Contest in Modeling (MCM) competition with a group of classmates. For my group, we decided to work on the project with probably the coolest problem title we had ever seen: Ultimate Brownie Pan.

When you cook brownies, the metal in the pan is an incredibly good heat conductor; it heats up faster than the brownie mix, so the pan will act as a mini heat source. As such, the part of the brownie mix that closest the pan will heat up faster, and cook faster than the rest of it (this is why the edges of brownies are always a bit chewier than the insides). However, this also means that some of the brownie edge will be more cooked than the other edge depending on the shape of the pan.

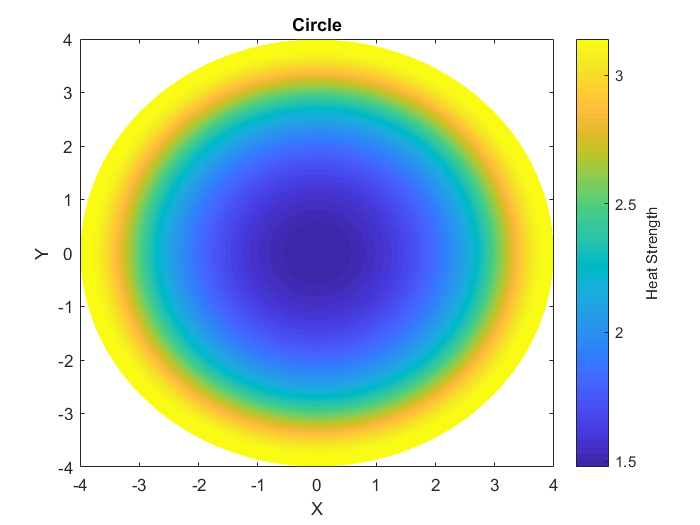

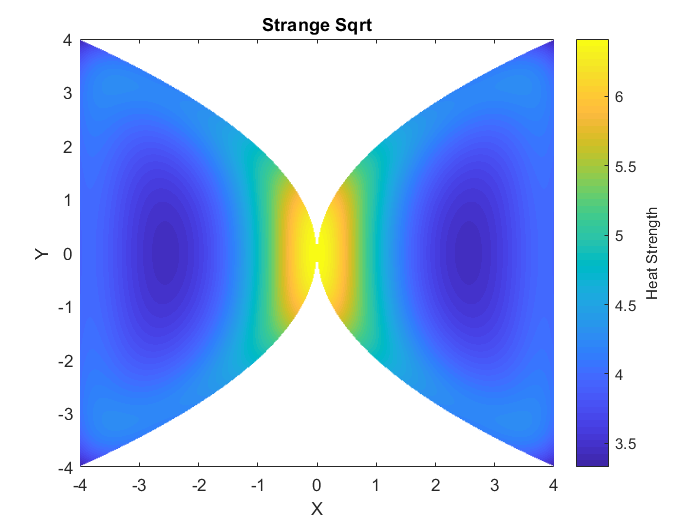

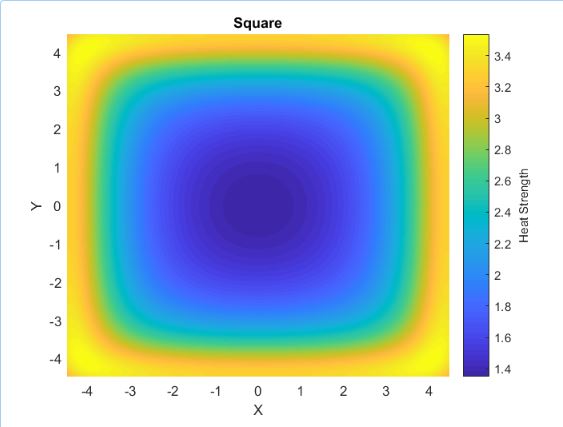

Hard to follow? Here are two examples: on a square pan, the heat builds up a lot stronger on the corners than the rest of the edges, meaning that they will be overcooked compared to the rest of the edges. On the other hand a circle heats up all of the edge points perfectly equal, meaning no section of the edge is over-cooked.

This was then coupled with the problem of space efficiency. While the circle was perfect for our heat problem, if you wanted to fit as many into an oven as possible, you’d be wasting a lot more brownie space compared to if you were using a perfectly square pan. That then leads us to our problem: What is the perfect brownie pan shape that minimizes wasted space, and cooks the edges as evenly as possible?

My main contribution to the team was the heat distribution algorithm, which is what I will be describing in this post. This algorithm focuses on radiated heat, which while not as strong as conducted heat, can provide a good potential “guesstimate” for what the conducted heat stregth will look like.

How to Model Heat without PDE’s

So the most important thing that we have to mention is about how heat travels. When heat moves, it follows something called the inverse square law. In essence, this means that as you move further and further away from the source of something, the strength that you feel from that source decreases by a factor of the inverse of the distance squared.

In essence, this means that as you move further and further away from the source of something, the strength that you feel from that source decreases by a factor of the inverse of the distance squared.

For example, say that we were 1 meter away from a fire. If we then moved to a distance of 3 meters away from the fire, we would only feel 1/4 the strength from before. This is because we are now two meters further away, and the inverse of that distance squared is 1/4. Note that this only applies for radiated heat, which is what I am modeling here.

This forms the foundation of what we’ll need to model the brownie pan heat, because heat follows the inverse square law. Normally when modeling heat, you need to know how the heat spreads in both space and time, but for our purposes we assumed that we had left the pan in the oven for a long period of time so that it was at the constant, max temperature. This provides a “worst case scenario” model, as the heat radiating out is a large as possible. As a nice side effect of this we no longer needed to solve partial differential equations (PDE’s), and could instead focus on what areas of the brownies would feel the most radiated heat.

To do this we had to slightly modify the inverse square law, so that it didn’t blow off to infinity as we got closer to the edges. To do this we assumed that when you touched the edge, the heat strength would be 1, so we could create the equation

where H is heat strength (unitless), and d is distance from the source to some point P.

Now imagine that our pan edge is broken up into a ton of tiny pieces, an each act as a heat source. We can say that the total heat strength at some point inside our pan is going to be equal to the sum of all the strengths of these small pieces.

Which, using a little Introductory Calculus, looks like a Riemann Sum! We can then turn this into an integral that goes along the edge of the pan, which using some Multivariate Calculus, we can recognize specifically as a line integral. A line integral takes the form of

This is fine and dandy, but how are we going to use this to heat up a pan?

The Calculus Behind Brownies

For our pans, we will assume that we can write their edges in terms of single variable functions of the form

This makes things super easy for us, as to perform a line integral we have to parameterize the curve in terms of a single variable t. To do this, we will just set our x to t, and then integrate on the bounds of x. We can use this to get that

This is the curve that we will integrate along to get the heat strength at a single point, so we now need to define the function of total heat strength for any (x,y) point inside of our pan. We will define this function as

Side note: we defined the function along a symmetrical interval to make the integration and such easier this can also be done on a non-symmetric interval, if you wanted to. The final thing we need to account for is the other 3 edges. After working through the first edge, the other three are trivial. We use the same integral, and add it to the results of the last integral for the bottom edge. You then can add the integral of the vertical curve for the left and right edges, which has a closed form for the integral (no numerical analysis required!). So the full form will be

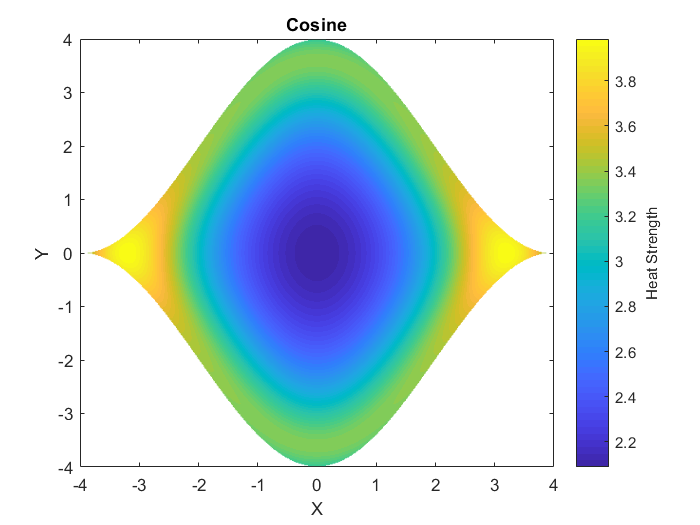

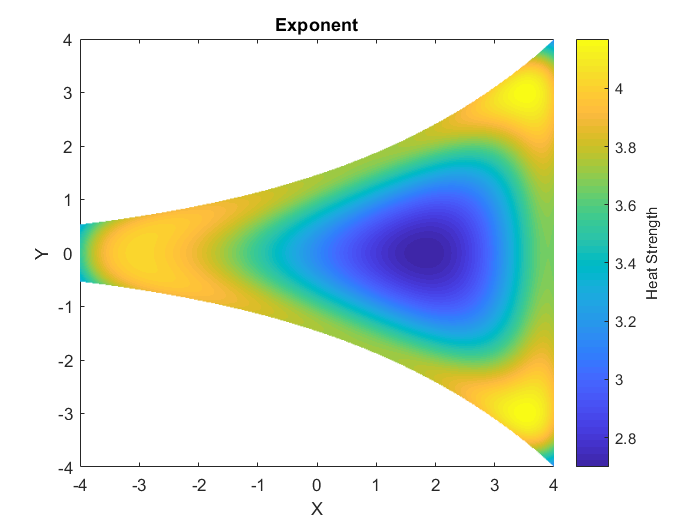

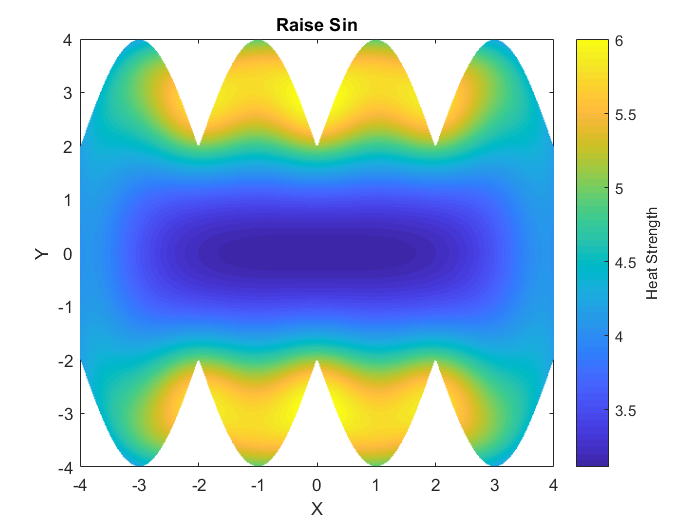

If we apply this formula to every point inside of the pan, congratulations! We have now solved the problem. From this we can get some pretty cool figures, such as the ones listed in the additional information section. I wrote some MATLAB code to solve the heatmaps shown in that additional information section, you can find the code here on my GitHub.